![]()

|

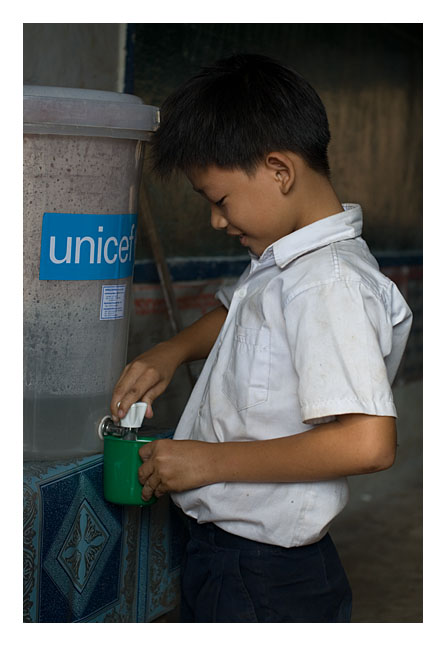

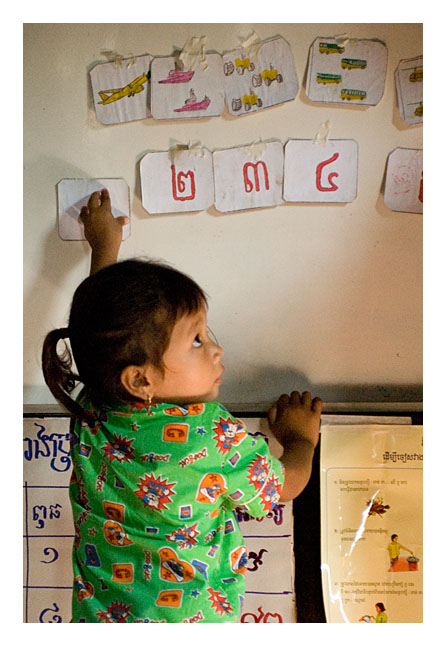

Imagine that children in our street were dying from diseases which could have been prevented by a simple vaccination. Imagine they were malnourished. That they dropped out of school in the first year because they had no preparation for learning. That they did not have access to a safe water supply. We would be outraged. There would be newspaper headlines. Questions asked in parliament. TV crews covering the story round the clock. Immediate action would be demanded. That this happens in other countries should be no less shocking, no more acceptable to us. We should be working just as hard to prevent it, wherever in the world it occurs. This is the work of Unicef in countries like Cambodia. A small group of us from my former employer visited Cambodia to see first-hand the difference this work makes to life in the country. My role was to take photos to publicise Unicef's work - these photos formed an exhibition and have been used in a wide range of Unicef publications, including the front cover of the 2008 Unicef diary. |

|

Background briefing |

|

Cambodia is a country of 14 million people, bordered by Thailand, Vietnam and Laos. Children form the majority of the population. Per-capita income is US$389. The garment industry provides a source of exports, with the USA taking 60% of production, though Cambodia faces increasingly tough competition from China and India. |

|

|

|

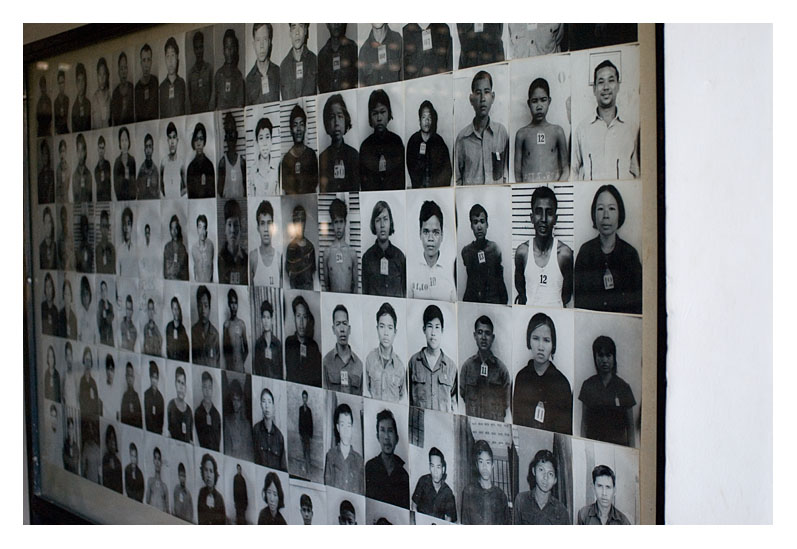

The new beginning was anything but. In a country of less than 10 million people at the time, around two million were killed (the exact number will never be known; estimates range from 1.5 million to 3.3 million.) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The challenges |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Education, education, education |

|

Less than half of children enrolled in schools complete primary school. 14% of them complete less than a year. Of those who do make it, the need to repeat grades means that it takes on average 10 years to complete a primary school education. One of the key solutions identified by Unicef is pre-school education, not only to help prepare children for school, but also to educate parents through their kids in things like safe sanitation. It was these projects we were visiting. |

![]()