![]()

| Sunday |

|

|

|

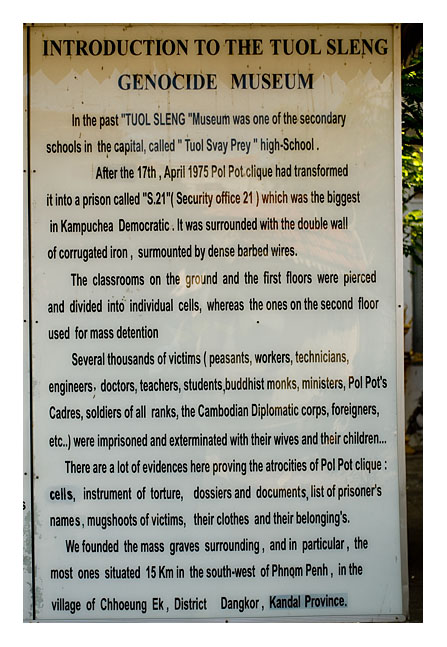

After 22 hours of travelling, and failing to get an early night, there was no expectation of either of us surfacing in the morning, so Unicef had offered us an optional visit to the National Museum in the afternoon. I decided instead to visit the genocide museum at Tuol Sleng, and Sabine opted to join me. This was a less pleasant visit, but the genocide is such a huge part of Cambodia's history, that I felt it had to be done. We hired a tuk-tuk driver for the afternoon. |

|

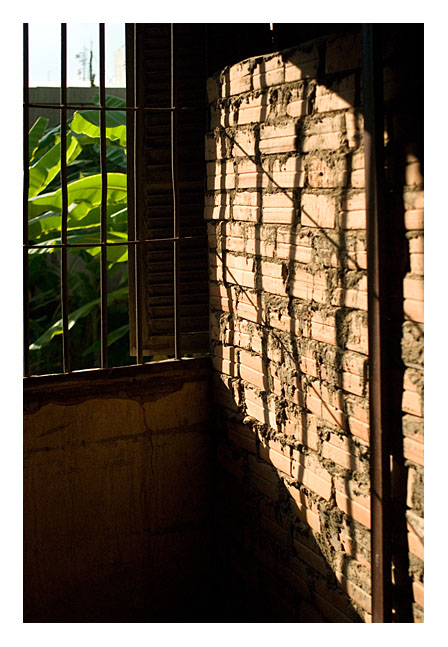

The guidebooks recommended a tour guide, to hear the stories of what we were seeing. Our guide did not spare us any details. He described the bodies found in rooms like this, where the Khymer Rouge had killed the remaining prisoners before they fled. |

|

Some flowers had been left on some of these beds - whether by family members or other visitors, I don't know. |

|

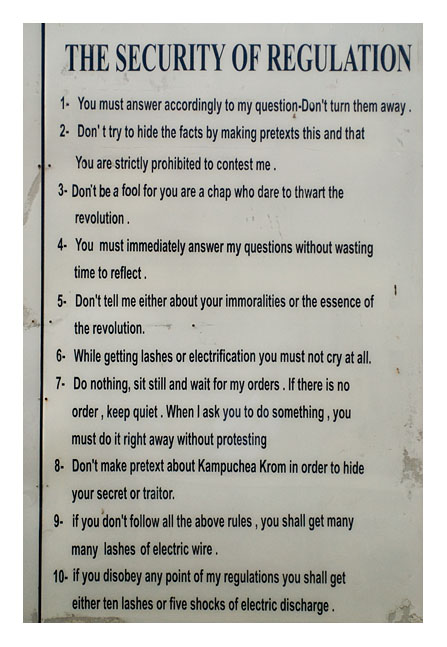

The rules of the prison had been translated into English: |

|

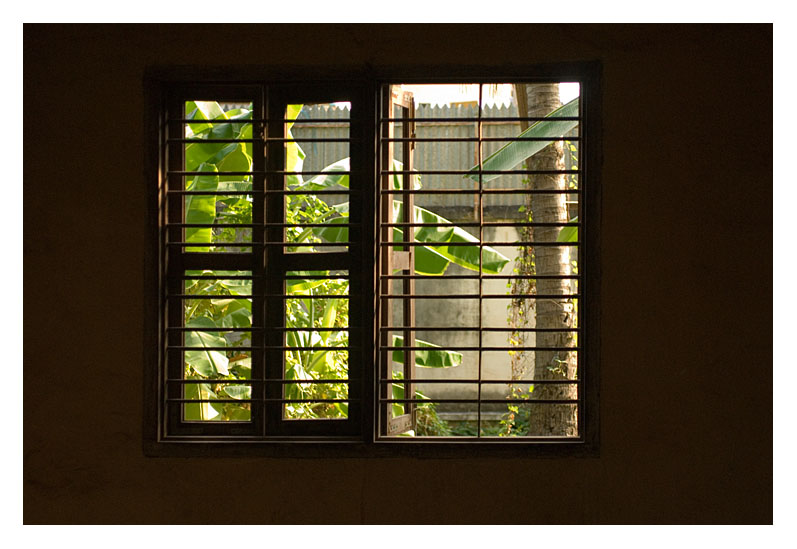

The former schoolrooms turned into cells were left pretty much exactly as they were at the time. |

|

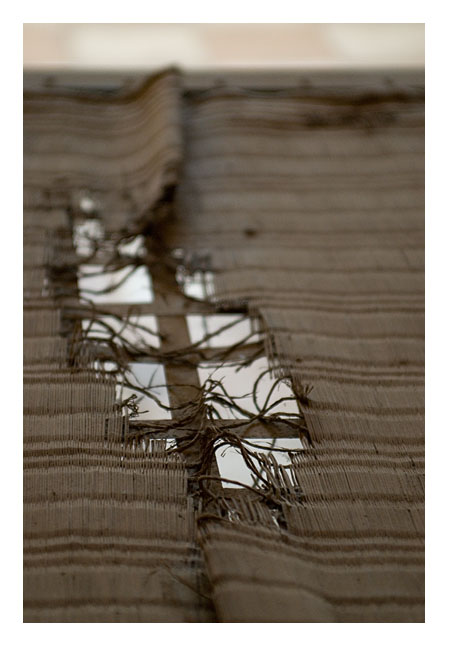

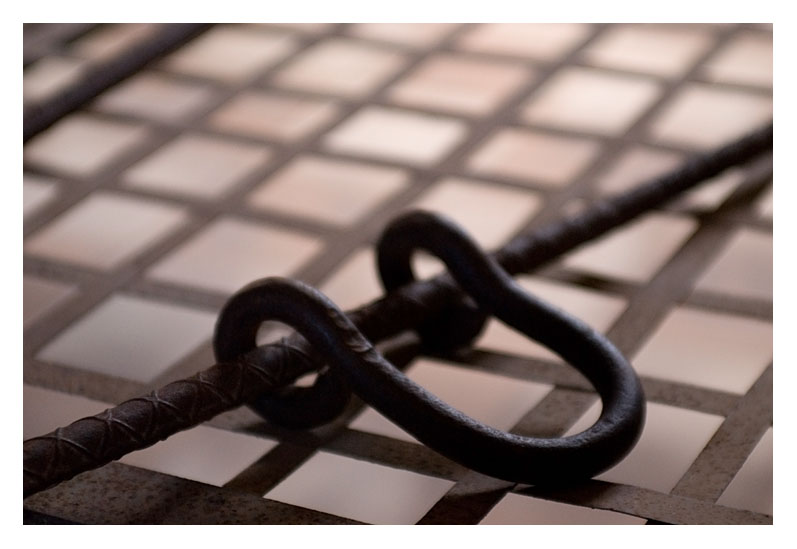

Prisoners were manacled, the manacles chained to the beds. A room with racks of them brought home a little bit of the scale of it. |

|

When it was a school, this frame held climbing ropes. When turned into a prison, people were hung from it to be tortured. |

|

There was a notice near the entrance asking people to be respectful of the souls of those who died there, and not to laugh inside the rooms. There were reminder signs at the entrances to the buildings. They scarcely seemed necessary: I cannot imagine anyone standing in these rooms laughing. |

|

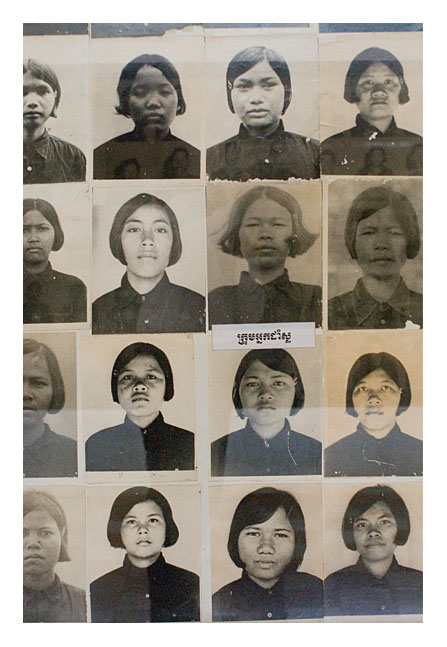

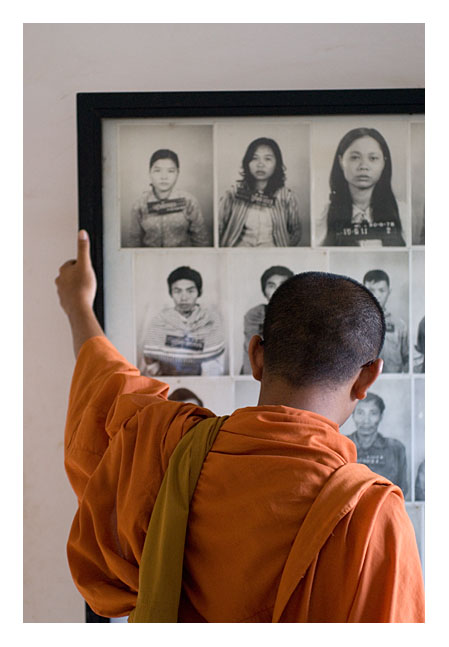

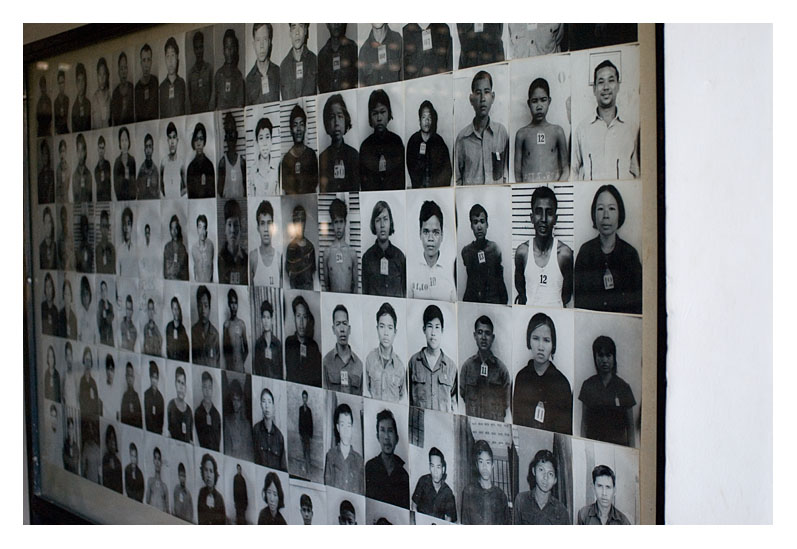

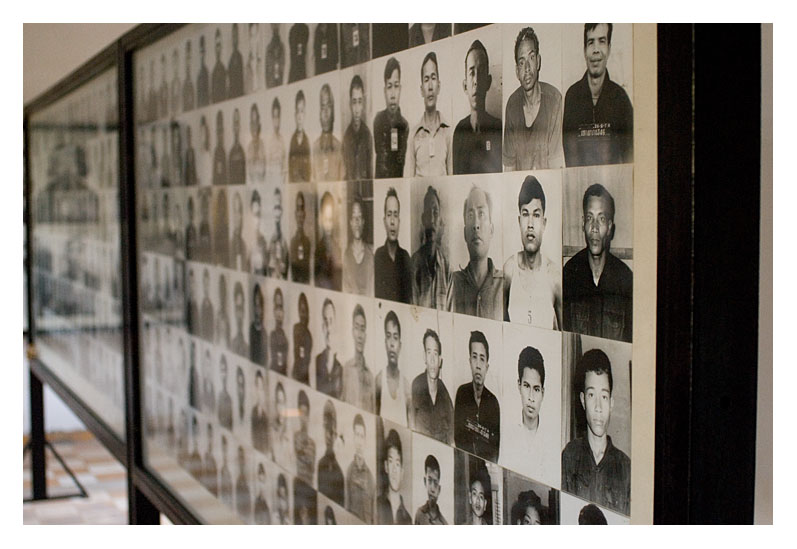

The next rooms we visited held photos of the victims. Every prisoner was photographed. They were sat on a special chair that held their body and head in a perfectly aligned fashion for the photos. Row after row of photos of victims. |

|

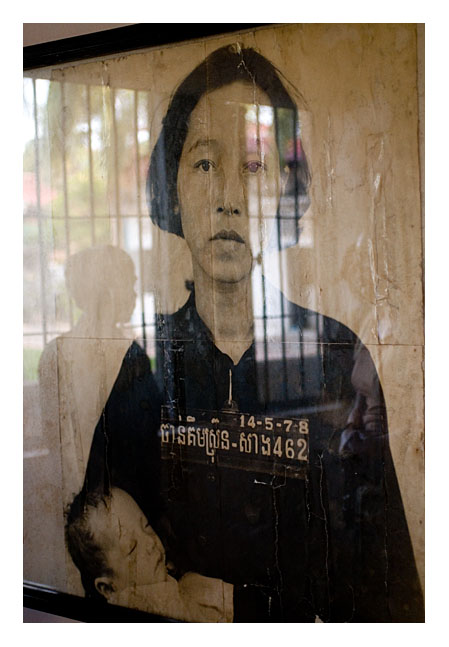

It was impossible to take in, to realise that each of these photos was a human being, imprisoned, tortured and killed. A few of the photos had been enlarged to poster size; those felt more real. |

|

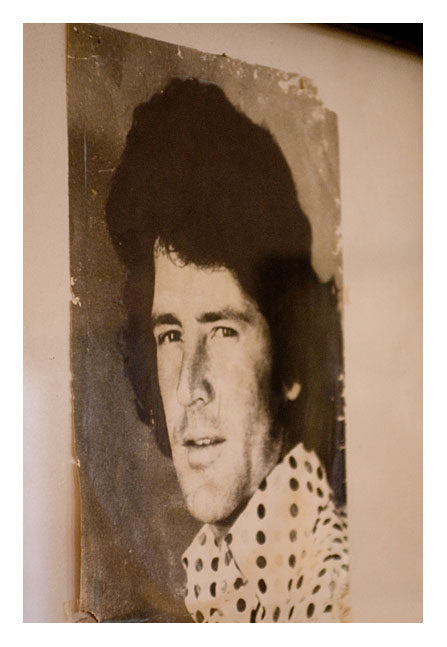

The babies too were killed. Any foreigners were considered spies. This journalist was arrested and killed. |

|

Most of the inmates were well aware of their fate. Some tried to commit suicide. After one woman threw herself from the third floor, barbed wire was fitted to prevent people jumping. |

|

Most of the cells were crude brick-built compartments in the former schoolrooms. |

|

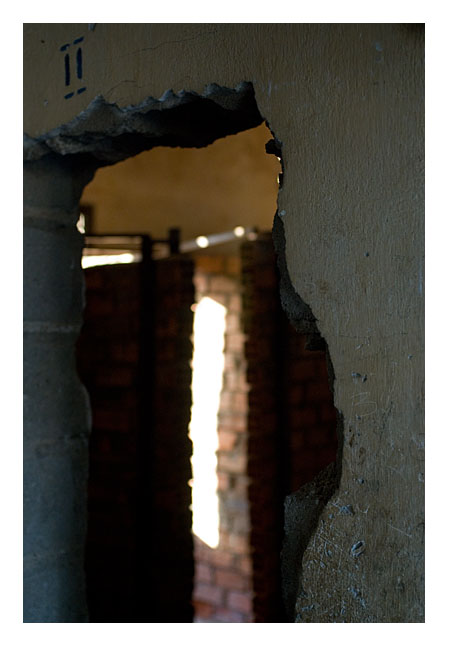

Doorways between the classrooms were created by simply knocking holes through them. |

|

Some of the torture equipment was still there. Our guide did not pull any punches in his descriptions of what went on. The details were so graphic I didn't feel able to reproduce them here. The cage below the frame held scorpions. |

|

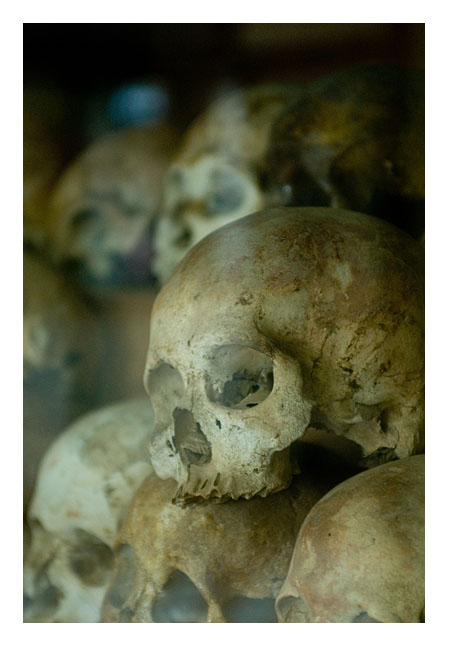

One room held some of the skulls, in glass cabinets. |

|

19,400 people entered Tuol Sleng. Just seven of them survived: |

|

One of these, the man on the right in this photo, became the director of the museum. The tour ended after about 30 minutes. Our guide told us we were free to explore the rest of the site. Sabine had a stronger stomach than me: she went on; I had seen enough. It was a relief to get back into our tuk-tuk and head back to normal Cambodian life. |

|

Mopeds and small motorcycles were the favoured form of transport, with entire families carried on them. |

|

It was rare to see fewer than three people on a moped. |

|

Unless it was being used to carry freight. |

|

No need to get off your moped to eat: |

|

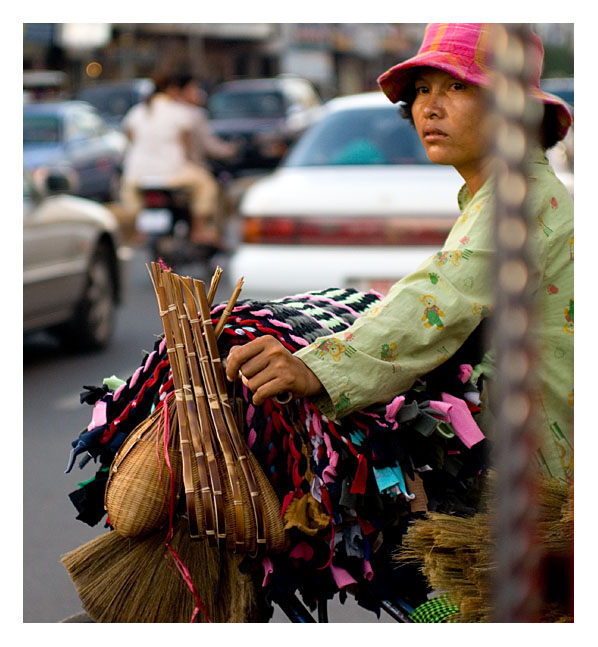

Bicycles were a relatively rare sight. Both rider and passenger are looking very carefully into the junction, which is well-advised here. Generally at junctions, nobody stops, they just aim for an empty space in it and keep going ... |

|

However, it generally seemed to work well. Rodney explained later that traffic law is pretty simple here: if you hit something smaller than you, the accident is your fault. Trucks thus give way to cars which give way to tuk-tuks which give way to motorcycles which give way to bicycles which give way to pedestrians. We headed off to the Russian market. Sabine went inside while I wandered around outside. |

|

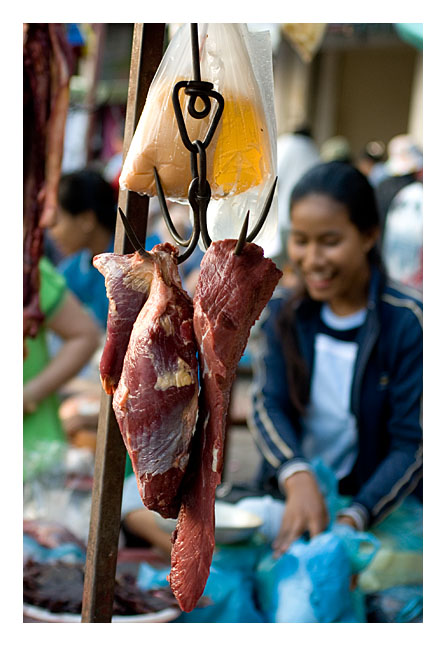

Meat hygiene is not very well developed. Meat was placed on bare tables with flies landing on it. |

|

But nobody could claim that prepared food is anything less than fresh. |

|

The rest of the group had arrived at various points in the day, and we all met up in the hotel lobby before Rodney from Unicef took us all out to dinner at a nearby restaurant. Cambodian food is similar to Thai, but less spicey. The dishes were simple but very tasty. |

|

Researchers are notorious for talking shop, but amazingly - with the help of a few other Unicef staff joining us - we did manage to talk mostly about Cambodia. Back to the hotel for nightcaps. Everyone drifted off to bed around midnight. We all had to earn our places on the trip through projects to promote the work. The good news about my deal was that, if I could keep up each night, I could have half of it - this blog - done by the time I got back home. The bad news was that while everyone else could hit the sack, I had a couple of hour's work left to do to process the photos and write the blog. As the week progressed, the sheer volume of photos I took meant writing the text while we travelled in Landcruisers and processing photos through dinner and into the early hours. This made for a very tiring trip, but with a very busy time back at work, it was my only real opportunity to get it done promptly. I'm a belt-and-braces man, so I'd brought both a spare camera body and an alternative to my primary lens. I'd also brought along a USB2 external hard drive to backup the photos each night. By the time that was done, it was 2am. |

![]()